Hardwiring Competition into Policy: A Blueprint for Thailand's Economic Future

Abstract

This article summarises the findings of a comprehensive peer review of Thailand’s competition policy framework, a high-level project conducted by VA Partners on behalf of the ASEAN Secretariat. The review, part of the ASEAN Competition Action Plan (ACAP) 2016–2025, focuses specifically on the effectiveness of the policy advocacy mandate of the Trade Competition Commission of Thailand (TCCT). The core argument presented is that proactive competition advocacy—shaping laws and regulations to be pro-competitive from their inception—is a more efficient and economically beneficial strategy than reactive enforcement, which addresses market harm only after it has occurred. This preventative approach represents a strategic shift from costly cures to intelligent economic design.

The international gold standard for this practice is the Republic of Korea, where a legally mandated consultation system requires all government agencies to seek input from the Korea Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) on potentially anti-competitive regulations. This systematic framework results in an impressive 80 per cent implementation rate for the KFTC’s recommendations, fostering a predictable and attractive investment climate.

In contrast, Thailand faces a significant gap between its legal mandate and its practical influence. While the Trade Competition Act B.E. 2560 (2017) empowers the TCCT to advise the Cabinet and other government agencies (Sections 17(11) and 17(12)), it fails to establish any procedural mechanism to ensure this advice is considered. The law is silent on whether agencies must consult the TCCT, respond to its recommendations, or justify their decision to disregard them. This creates a one-way, non-binding advisory function, rendering the TCCT a voice without a guaranteed audience.

Our extensive field study, involving consultations with all key stakeholders—from the Board of Investment and sector regulators to the Council of State and private sector leaders—confirmed this structural weakness. We found that awareness of the TCCT’s advocacy role is alarmingly low, engagement is ad hoc and informal, and a deep-seated culture of jurisdictional autonomy leads powerful agencies to resist external input. This results in an 'accountability vacuum' where inconvenient competition advice can be quietly ignored without consequence.

To address this, we propose a pragmatic, three-tiered approach to forge a 'bilateral and necessary' framework. The optimal solution is to amend the Trade Competition Act to create a mandatory consultation process. A viable alternative is a binding Cabinet Resolution, while immediate progress can be made through strategic bilateral agreements with high-impact agencies. The centrepiece of this reform is a ‘comply-or-explain’ mechanism, which would legally obligate agencies not only to consult the TCCT but also to provide a formal, public justification for deviating from its advice.

Implementing these reforms is not merely a domestic priority. It is a critical step for Thailand to fulfil its commitments under the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint, positioning the nation as a regional leader in economic governance. By hardwiring competition principles into the machinery of government, Thailand can create a more dynamic, resilient, and prosperous economy, offering a valuable blueprint for its ASEAN peers.

This analysis stems from a comprehensive peer review of Thailand’s Trade Competition Commission (TCCT), a high-level policy project VA Partners was commissioned to undertake on behalf of the ASEAN Secretariat. The review is a key component of the ASEAN Competition Action Plan (ACAP) 2016–2025, a regional framework designed to strengthen and harmonise competition policy across the ASEAN Economic Community. Following a pilot review of Malaysia, Thailand was selected as the second ASEAN member to undergo this voluntary process of mutual evaluation, which serves as a tool for institutional learning and capacity building rather than a formal compliance mechanism. Our specific mandate was to assess the effectiveness of the TCCT’s role in policy advocacy—its power to shape government policy and regulation to foster competition—as established under Sections 17(11) and 17(12) of the Trade Competition Act B.E. 2560 (2017).

The Competition Compass: Why Prevention Outperforms Cure

In short, it is far more effective for a country's economy to prevent anti-competitive regulations from being created than it is to fix the damage after the fact.

In the architecture of a modern, dynamic economy, competition policy serves a dual function. It is most commonly understood in its reactive capacity: an enforcement tool deployed to investigate and remedy anti-competitive conduct after market harm has occurred. While essential, this ex post function is analogous to treating a malady that has already taken hold. A more sophisticated and economically efficient approach lies in the proactive, ex ante role of competition policy—shaping the regulatory environment to prevent market distortions from arising in the first place. For governments, embracing this preventative philosophy is the difference between being a market policeman and a market architect. It is a strategic shift from costly cures to intelligent design, ensuring that the very rules of the game foster innovation, efficiency, and consumer welfare from their inception.

This proactive function is known as policy advocacy. The International Competition Network (ICN), the leading global body for competition authorities, defines it as the formal engagement with policymakers, regulators, and legislatures to ensure that competition principles are integrated into the design and reform of public policies. It is a high-level, technical discipline distinct from general public awareness campaigns. It seeks to hardwire pro-competitive thinking into the machinery of government, thereby reducing the need for resource-intensive enforcement actions and cultivating an economic ecosystem where fair and open markets are the norm, not the exception. The ultimate goal is to create a virtuous cycle where well-designed policies foster competitive markets, which in turn drive sustainable economic growth.

The tangible benefits of such a system are not theoretical. The Republic of Korea provides the international gold standard for effective competition advocacy. Under Article 120 of its Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act (MRFTA), all South Korean government agencies are legally required to consult the Korea Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) before enacting any legislation or regulation that may restrict competition. This is not a polite suggestion but a mandatory step in the policymaking process. The results are profound. This systematic, legally-enshrined framework yields an 80 per cent implementation rate for the KFTC’s recommendations. This figure is more than a mere statistic; it is evidence of a system where competition advice is not only heard but is consistently acted upon, shaping the national economic landscape for the better.

This high rate of adoption signifies a deep institutional respect for the competition authority's expertise, a level of trust that becomes a tangible economic asset. For businesses, it creates a predictable and stable regulatory environment, reducing the "regulatory risk" that can deter long-term investment. When investors are confident that market rules will be designed to be pro-competitive, it lowers the cost of capital and encourages the kind of dynamic investment that fuels innovation and job creation. The KFTC’s success demonstrates that when a competition authority evolves from a reactive enforcer to a proactive architect, it does not merely prevent a few anti-competitive regulations; it helps to build a more attractive, resilient, and prosperous national economy.

The Thai Dilemma: A Mandate Without a Mechanism

While Thailand’s competition law provides the authority to advise the government, our review found it lacks the procedural teeth to ensure this advice is systematically heard or considered, creating a mandate without a mechanism.

Thailand’s legal framework contains the nascent architecture for such a system. The Trade Competition Act B.E. 2560 (2017) (TCA) formally empowers the Trade Competition Commission of Thailand (TCCT) with an advocacy mandate. Specifically, Section 17(11) authorises the TCCT to provide opinions to the Cabinet on government policies, while Section 17(12) allows it to make recommendations to other government agencies on rules and regulations that may impede competition. On paper, these provisions grant the TCCT the authority to act as the government’s competition compass.

However, our comprehensive peer review, conducted on behalf of the ASEAN Secretariat, reveals a critical gap between this statutory authority and its practical influence. The core of the problem lies in the legislative drafting: the TCA establishes the power to advise but fails to create any corresponding mechanism for that advice to be systematically considered. The law is "drafted in broad terms" and, crucially, "is silent on whether the public bodies receiving TCCT opinions are required to respond or provide a justification if they decide to disregard the recommendations". This legislative silence creates a one-way, non-binding advisory function. It is a mandate without a mechanism, a voice without a guaranteed audience.

The findings from our extensive field study, which involved in-depth consultations across the entire Thai policy ecosystem, confirm this structural weakness. Our engagement included key sector regulators such as the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) and the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC); critical economic policymakers like the Board of Investment (BOI) and the Ministry of Finance; legal gatekeepers including the Council of State; and a wide cross-section of the private sector and academia. The evidence gathered was consistent and clear.

Across the board, awareness of TCCT’s advocacy role is alarmingly low. Officials at powerful agencies, including the BOI, whose investment incentives fundamentally shape market structures, and the ERC, which governs competition in the vital energy sector, confirmed they had little to no familiarity with TCCT’s mandate. Where engagement does occur, it is overwhelmingly described as "ad hoc, reactive, and informal". TCCT may be invited to a hearing or consulted via an informal telephone call, but this participation is symbolic rather than substantive. Its advice is procedurally acknowledged but rarely integrated into final policy outcomes. This dynamic is compounded by a deeply ingrained culture of "jurisdictional autonomy," particularly among powerful, constitutionally-established regulators like the NBTC. These bodies view competition as a secondary concern to be managed internally, resisting what they perceive as encroachment from an external authority.

This situation has created what can best be described as an 'accountability vacuum'. The absence of a legal duty for an agency to respond to TCCT's advice, combined with the fact that TCCT’s opinions are not made public, means that inconvenient recommendations can be quietly ignored without any political or reputational cost. This vacuum ensures that TCCT’s influence is contingent on the goodwill of other agencies rather than on institutional design, rendering its statutory mandate largely symbolic.

Furthermore, TCCT’s challenges are not unique within the Thai administrative state. Our review found that other advisory bodies, such as the Consumer Protection Board (CPB) and the Office of SMEs Promotion (OSMEP), face the identical problem of having their non-binding recommendations routinely disregarded. This points to a deeper, systemic governance culture that institutionally marginalises advisory functions in favour of siloed, executive decision-making. Therefore, addressing the weakness in the TCA is not merely a technical fix for one agency; it is an opportunity to catalyse a broader modernisation of Thailand’s policymaking process towards greater evidence-based collaboration.

The recent successful collaboration between TCCT and the Electronic Transactions Development Agency (ETDA) on regulating digital food delivery platforms serves not as a contradiction of this systemic weakness, but as a powerful confirmation of it. That success was an exception born of crisis—a flood of complaints from restaurant operators—which forced the two agencies to recognise their mutual need for each other's expertise. It demonstrates that Thai agencies possess the capacity for effective, purpose-driven collaboration. The objective of reform must be to make the conditions of that success—a bilateral, evidence-based dialogue—the rule, not the exception.

The Solution: Forging a 'Bilateral and Necessary' Framework

To fix this, the solution lies in creating a formal, 'bilateral and necessary' dialogue, where government agencies are required to consult the TCCT and transparently justify their policy choices.

The solution to transforming TCCT’s advocacy from a symbolic gesture into a substantive force for economic good lies in redesigning the process itself. The system must evolve from a unilateral, optional suggestion into a bilateral, necessary dialogue. This requires the creation of a formal, systematic consultation mechanism that ensures competition analysis is not just offered, but is actively considered at the heart of policymaking. Based on international best practice and the specific context of Thailand’s governance structure, we propose a pragmatic, three-tiered approach to achieve this reform.

Tier 1 (Optimal): Legislative Amendment. The most robust and permanent solution is to amend the Trade Competition Act directly. With the Act currently undergoing a second amendment process in a parliamentary special committee, there exists a rare window of opportunity to incorporate mandatory consultation provisions. This would institutionalise the process, giving it a clear legal foundation and durability that transcends political cycles.

Tier 2 (Viable): Cabinet Resolution. If immediate legislative amendment proves politically unfeasible, a binding Cabinet Resolution can establish a mandatory consultation requirement across the executive branch. This approach has precedent in Thailand and can be implemented relatively quickly, creating immediate obligations for ministries and government agencies to engage with the TCCT on relevant policy proposals.

Tier 3 (Immediate): Strategic Bilateral Agreements. Irrespective of broader reforms, the TCCT can and should immediately begin forging formal, binding protocols with high-impact agencies. Priority targets should include the Department of Foreign Trade, to ensure competition analysis is integrated into anti-dumping investigations, and the Board of Investment, to assess the competitive effects of major investment incentive packages.

The centrepiece of this new framework, regardless of the tier in which it is implemented, is the introduction of a ‘comply-or-explain’ mechanism.1 This principle would legally obligate government agencies not only to consult the TCCT on policy proposals with potential competition implications but also to provide a formal, public, written justification if they choose to deviate from the TCCT’s recommendations. This simple but powerful change transforms the interaction from a monologue into a genuine dialogue. It forces policymakers to weigh competing objectives transparently and creates a record for public and parliamentary scrutiny, thereby closing the accountability vacuum.

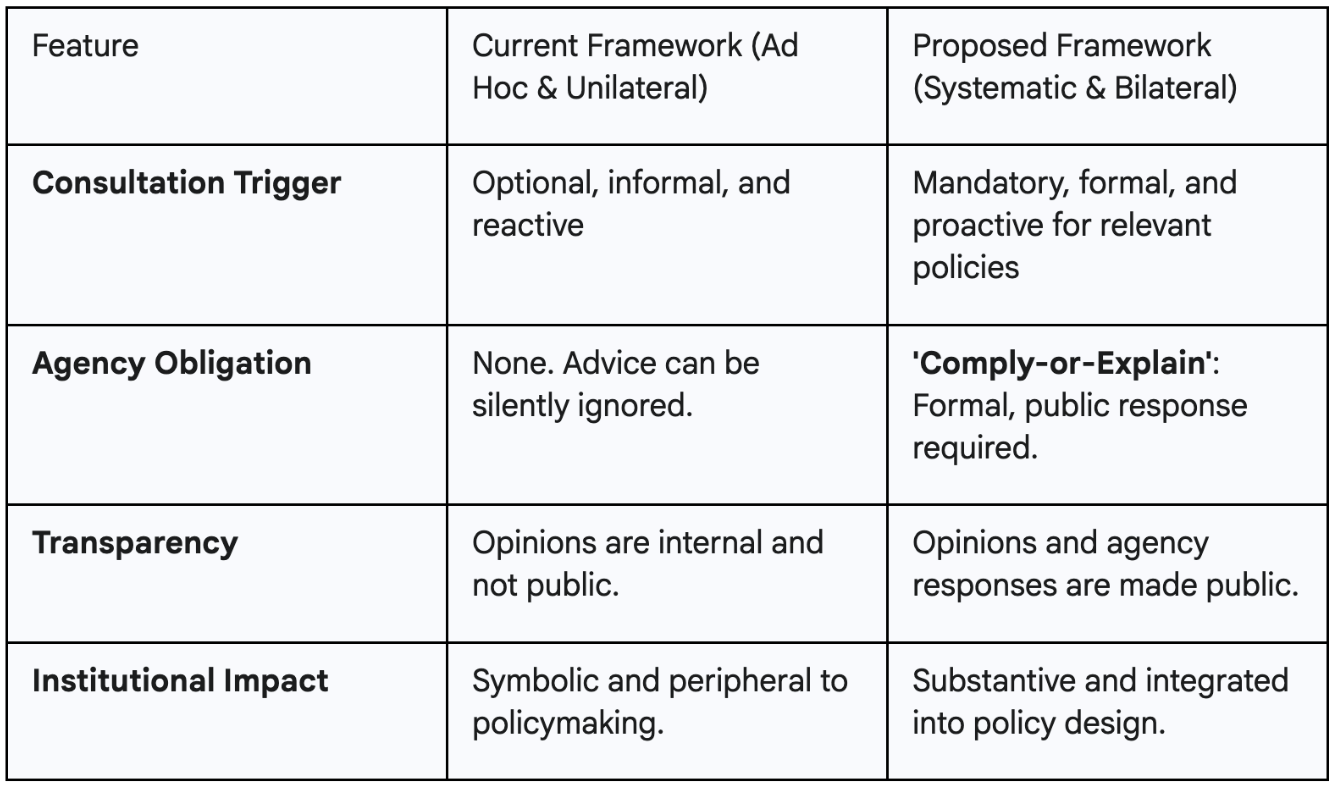

To ensure the system is both effective and efficient, this bilateral mechanism must be paired with a refined standard for when government actions can legitimately restrict competition. We recommend amending Section 4 of the TCA to narrow the current blanket exemption for government agencies and state enterprises. The new standard should stipulate that such exemptions apply only when a restriction on competition is proven to be "necessary and proportionate" to achieve a legitimate public interest objective—such as national security or public health—that cannot be achieved through less anti-competitive means. This introduces a public interest test that forces a rigorous evaluation of trade-offs, ensuring that competition is not sacrificed for policy goals that could be met in a more market-friendly manner. The proposed changes are summarised in the table below.

Table 1: Transforming Competition Advocacy in Thailand

A Regional Blueprint: Shaping ASEAN Competition Policy

Ultimately, strengthening Thailand’s competition advocacy framework is not just a domestic reform; it is a vital contribution to the nation’s strategic role within the ASEAN Economic Community.

The analysis and recommendations presented here are drawn from a comprehensive peer review that VA Partners was commissioned to conduct on behalf of the ASEAN Secretariat. This context is crucial, as the imperative to strengthen Thailand’s competition advocacy framework extends beyond domestic economic management. It is intrinsically linked to the nation’s strategic commitments and its role within the broader regional economic architecture.

This work aligns directly with the core objectives of the ASEAN Competition Action Plan (ACAP) 2016–2025, a foundational document of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Blueprint. The ACAP identifies the establishment of effective national competition regimes as a critical element for successful regional integration, necessary to support efficiency, foster innovation, and protect consumer welfare across the bloc. By institutionalising a robust policy advocacy mechanism, Thailand would not only enhance its own economic governance but also take a significant step towards fulfilling its regional obligations.

The challenges identified within Thailand’s current system—a statutory mandate undermined by procedural gaps, a culture of institutional silos, and the marginalisation of advisory functions—are not unique. They represent common hurdles faced by many developing and emerging economies seeking to embed competition principles into their policymaking processes. Consequently, the proposed solutions—a tiered approach to reform centred on a mandatory, transparent, ‘comply-or-explain’ mechanism—offer a valuable and practical blueprint for other ASEAN Member States.

By adopting these reforms, Thailand has an opportunity to transition from a regional peer to a regional leader in competition policy best practice. This leadership can help de-risk the politics of similar reforms in neighbouring countries. When domestic proposals are framed as steps towards meeting shared regional commitments under the ACAP, it provides powerful external validation that can help policymakers overcome internal resistance from entrenched interests. The narrative shifts from a narrow, domestic power struggle to a collective, forward-looking effort to modernise the region’s economic governance in line with international standards.

In an era of intensifying geopolitical competition and a global race to attract high-quality foreign direct investment, a predictable, transparent, and pro-competitive regulatory environment is no longer a mere advantage; it is a strategic necessity. Robust competition advocacy is a critical tool for building such an environment. It signals to the international investment community that a country is serious about maintaining a level playing field and making evidence-based policy decisions. For Thailand, and for ASEAN as a whole, hardwiring competition into the DNA of government is not just good domestic policy—it is a vital component of a compelling strategy for regional competitiveness and long-term prosperity.